The story of this blog so far tells how humanity strove to become a controlling force over nature. It is not a noble story; but neither can it be said to be an ignoble story. It is a mixed blessing. The despoiling of nature can be seen as a consequence of something greater—a seemingly pre-destined unfolding of the quest for consciousness to explain reality. In time it spans about three centuries, beginning when philosopher René Descartes in France and scientist/mathematician Isaac Newton in England opened up a vision of an Earth understandable by human reason. From there it was but a short step for entrepreneurial minds to assert that nature could be made to serve human purpose. Of course, we know now that this was wrong, but the course was set and followed. When seemingly unlimited sources of energy were discovered and combined with human ingenuity, a powerful new civilization spread around the world. We called it industrialism and today it denominates everything.

Industrialism became a new way of being on the Earth—one that could more fully exploit the bounty of nature. Sustained and accelerated by new concepts of specialized productive labour producing goods for sale in free markets, it came to be known as capitalism. A new discipline, economics, developed. It aimed to explain and manage this new form of human organization. And by and large the system worked well for many millions of people in many countries over many generations—but only if enterprise was disconnected from the limiting constraints of nature. The idea of limits was not compatible with a newfound sense of progress.

The new discipline of economics was embraced by politicians, industrialists and business leaders. Their minds were bemused into believing that civilization could defy the cycles and constraints of nature and surge forward into the future as a flood of never ending growth. Again, it seemed, except for periodic setbacks, to work well. Until we reached the 21st century.

Now evidence abounds that industrialism as we have known it is not sustainable very much further into the future. For those of us who lived the majority of our lives in the 20th century this is not a serious issue. The familiar trappings of material abundance will see us out. But for those of us who have a mind to care about what lies in store for our grandchildren the question is, “Which way do we go from here?”

The Dream of the Earth

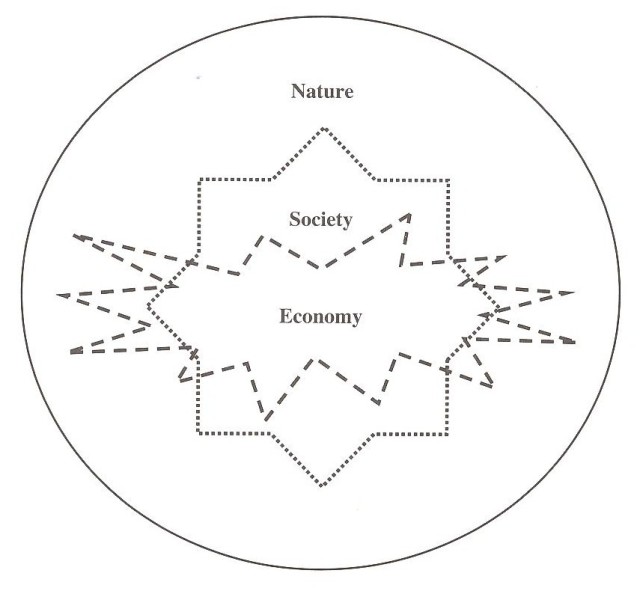

Increasingly, the answer to that question is being sought in the science of ecology—in the context of how human activity is to be accommodated within the natural systems of the planet, including all other life forms that depend, along with us, on the healthy functioning of those ecosystems. Which brings me to the third E in the framework of this blog: Ecology as a determinant of human destiny.

We should understand from the outset that our consideration of ecology needs to go deeper than treating it as an objective science. A science it certainly is, and therefore amenable to the process of empirical investigation. As such, it is yielding valuable understanding about how ecosystems work and what that means for human settlement and activity. However, at a deeper level, underlying the collection and interpretation of scientific data, there is a profound sense that in this inquiry we are venturing into the realm of the sacred—the place where human reflection reaches to connect to something larger than itself. This is the place where I wish to begin.

To guide us into this reflection I can think of no better source than Thomas Berry, who was described by Newsweek as “the most provocative figure among this new breed of eco-theologians. . . a solitary American monk whose essays have aroused environmentalists like a voice crying for the wilderness.”

In 1988 a collection of Berry’s essays was published under the title, The Dream of the Earth. In the essay from which the book takes its title he sets out both the despair and hope for humanity. He begins gently then builds forcefully to his central argument.

“In this late twentieth century we are somewhat confused about our human situation. We need guidance. Our immediate tendency is to seek guidance from our cultural traditions. . . [But] our cultural traditions, it seems, are themselves a major source of our difficulty. It appears necessary that we go beyond our cultural coding. . . we need to go to the earth, as the source whence we came, and ask for its guidance, for the earth carries the psychic structure as well as the physical form of every living being upon the planet. . . The human is less a being on the earth or in the universe than a dimension of the earth indeed of the universe itself.”

In these few short sentences Berry has established the central argument of the ecological as opposed to the industrial view of humanity. The human being is not just physically but psychically connected to the earth. Then he goes on to describe the consequences of ignoring that bond.

“Our secular, rational, industrial society, with its amazing scientific insights and technological skills, has established the first radically anthropocentric society and has therefore broken the primary law of the universe, the law of the integrity of the universe. . . The immediate advantages of this new way of life for its prime beneficiaries have been evident throughout these past two centuries. But, now, suddenly, we begin to experience disaster on a scale never before thought possible.”

From there Berry goes on to catalogue what we thought were our great achievements “to re-engineer the planet” all in the name of “this magical word progress!” But what we did not understand was that this sense of achievement was grounded in illusion.

“What we seem unwilling or unable to recognize,” says Berry, “is that our entire modern world is itself inspired not by any rational process, but by a distorted dream experience, perhaps by the most powerful dream that has taken possession of the human imagination. Our sense of progress, our entire technological society, however rational in its functioning, is a pure dream vision in its origin and in its objectives. . . The story of this dream vision. . . has become the central story of the human community. . . The difficulty of our times is our inability to awaken out of this cultural pathology.”

And what are the physical manifestations of this cultural pathology? Berry asserts their gravity in short, sharp, stabs of acid prose.

“We are changing the chemistry of the planet. We are altering the great hydrological cycles. We are weakening the ozone layer that shields us from cosmic rays. We are saturating the air, the water, and the soil with toxic substances so that we can never bring them back to their original purity. We are upsetting the entire earth system that has, over some billions of years and through an endless sequence of experiments, produced such a magnificent array of living forms, forms capable of seasonal self-renewal over an indefinite period of time.”

Strong words, but Berry is just warming to his subject!

“The disastrous consequences [of our attitude and behaviour] on the integral functioning of the earth [and] on our human destiny. . . are now becoming manifest. The day of reckoning has come. In this disintegrating phase of our industrial society, we now see ourselves not as the splendour of creation but as the most pernicious mode of earthly being. We are the termination not the fulfillment of the earth process. . . We are the affliction of the world, its demonic presence. We are the violation of earth’s most sacred aspects.”

However, as deep as Berry’s despair of the human impact on the planet might be, he is not without hope. He turns next to considering the way out.

“In moments of confusion such as the present, we are not left simply to our own rational contrivances. We are supported by the ultimate powers of the universe as they make themselves present to us through the spontaneities within our beings. . . The supreme need of our times is to bring about a healing of the earth through this mutually enhancing human presence to the earth community. To achieve this mode of presence, a new type of sensitivity is needed, a sensitivity that is something more than romantic attachment to some of the more brilliant manifestations of the natural world, a sensitivity that comprehends the larger patterns of nature, its severe demands as well as its delightful aspects, and is willing to see the human diminish so that other life forms might flourish.”

Now he has come to it. Human survival depends on our rethinking of the intrinsic values of the natural world, as well as the value we might accord to our own human culture.

“Two radical positions—the industrial and the ecological—confront each other, with survival at stake: survival of the human at an acceptable level of fulfillment on a planet capable of providing the psychic as well as the physical nourishment that is needed. No prior struggle in the course of human affairs ever involved such issues at this order of magnitude. If some degree of reconciliation has taken place, it remains minimal in relation to the changes that are needed to restore a viable mode of human presence to the earth.”

That was said in 1988. Some progress has been made since then in understanding our predicament, but not a lot in correcting it as Berry would have us do. The last paragraph of his essay resonates with his still unanswered challenge.

“In relation to the earth, we have been autistic for centuries. Only now have we begun to listen with some attention and with a willingness to respond to the earth’s demands that we cease our industrial assault, that we abandon our inner rage against the conditions of our earthly existence, that we renew our human participation in the grand liturgy of the universe.”

The Great Work

Writing a decade later at the turn of the new millennium, Berry published his manifesto for what we must do, and called it The Great Work: Our Way into the Future (1999). Reflecting on the great work of previous periods in human history—like “the Great Work of the classical Greek World” that created the Western humanist tradition, and “the Great Work of Israel in articulating a new experience of the divine in human affairs”—Berry sets out the challenge for our own time in clear unambiguous terms: “The Great Work now, as we move into a new millennium, is to carry out the transition from a period of human devastation of the Earth to a period when humans would be present to the planet as in a mutually beneficent manner.”

Berry has an epochal view of this moment in time: “The Great Work before us. . . is not a role we have chosen. It is a role given to us, beyond any consultation with ourselves. We did not choose. We were chosen by some power beyond ourselves for this historical task.” In Berry’s sense of history civilization moves forward through epochal moments, when conditions have regressed into a “Dark Age” of ignorance and new generations step forward to lead humanity out of its impasse. At these times the generations alive must see themselves not only as chosen to participate in the great work to be done, but as sustained “and cared for and guided by these same powers that bring us into being. . . We cannot doubt that we too have been given the intellectual vision, the spiritual insight, and even the physical resources we need for carrying out the transition that is demanded of these times.”

What an inspiration these words of Thomas Berry are to those who read this blog and to the countless thousands of others worldwide who are stepping forward to halt the “industrial assault” on the natural world! In such an inspired vision lies the best hope for our grandchildren. Every one of us has a role to play—and we are never acting alone, but in unison, in a “capacity for relatedness,” which is woven into the fabric of the universe in a wondrous dance of participation.

Berry’s contribution to the transcendent change for which he argues is much greater than his foundational concepts about the human-nature continuity. He has much to say in The Great Work about the specific transformations required in industrially acculturated institutions: reforms in education, jurisprudence, ethics, governance and corporate activity. These specifics will be covered in later posts as we explore initiatives to be undertaken in the E of enterprise in the framework of this blog. For now we need to understand the foundational insights articulated so passionately by Berry that must underlie the actions we need to take.

Commenting on Berry’s great contribution to transformational ecological thinking, environmentalist Richard Louv in The Nature Principle: Reconnecting with Life in a Virtual Age (2011) cites an interview with Berry in the journal Parabola in 1999 in which he spoke about the inner core of his belief: “If we don’t have certain outer experiences, we don’t have certain inner experiences, or at least, we don’t have them in a profound way. We need the sun, the moon, the stars, the rivers and the mountains and the birds, the fish in the sea, to evoke a world of mystery, to evoke the sacred. It gives us a sense of awe. There is a response to the cosmic liturgy, since the universe itself is a sacred liturgy.”

What does he mean, “the universe itself is a sacred liturgy?” We must remember that Thomas Berry was a Roman Catholic priest of the Passionist order, and as such liturgy—the prescribed order for public worship—was important to him. But Berry, the cosmologist, saw beyond the confines of his Christian tradition, to the great new creation story of the universe revealed by modern science. And his interpretation of the scientific account of the Big Bang and the formation of the galaxies carries with it the mystical insights of the spiritual mind.

Not only, he says, was ”the flaring forth of the primordial energy” the beginning of the Earth story, it was also “the beginning of the personal story of each of us, since the story of the universe is the story of each individual being in the universe.” The sacred liturgy of the universe is the revelation over eons of time that “inherent in the original flaring forth” were the “shaping forces” that “brought forth the galaxies, the Earth, the multitude of living species” and also the human intelligence that now reveals the new creation story as the universe becomes conscious of itself. We, humans, are the consciousness of the universe fully invested with all of its transcendent magnificence, and we are not about to compromise our sacred part in this new creation story by allowing the lesser aspects of our intelligence that support the “assault of industrialism” to triumph over our sacred heritage.

If you understood all that, then you will know why Thomas Berry, though he was filled with despair at what he saw happening to the natural world during his lifetime, was optimistic at the end of his life about prospects for the future. Richard Louv, whom I mentioned above as the author of The Nature Principle, first met Berry in 2005 when Berry was ninety-one years old. Right away, Louv reports, the old man began to talk about the future: “Everything we discuss now should be about the twenty-first century. . . The great work of the twenty-first century will be to reconnect to the natural world as a source of meaning.” A few years later in 2009 Louv visited Berry for the last time, shortly before his death. Even at that great age, the grand old eco-theologian said that he felt an urgency to “go out into the natural world every day, no matter what the conditions are” because “the giftedness continues.”

Uprisings for the Earth

I have devoted so much space in this post to the teaching of Thomas Berry because his insights go to the heart of what we must do in the decades ahead to preserve a viable future for humanity in the natural world. Berry sensed an “inner rage” in human beings of the industrial age against nature because we want to escape the limits that nature imposes. We want to be better than nature. But what we must be is in nature: to accept the earthquakes, the hurricanes, the pestilences and the privations along with the awe and wonder and the marvellous nutritional abundance of the land and the oceans. Indeed, “the giftedness continues.” Our task is to learn again how to receive and use the gifts.

Another voice to add resonance to Berry’s message is that of artist/sculptor and environmentalist Osprey Orielle Lake, who brings her feminine sensitivity to the call for humanity’s reconnection to the natural world in Uprisings for the Earth: Reconnecting Culture with Nature (2010). Taking off from Berry’s distinction between our inner and outer worlds, she says simply: “My thesis is this: whether we seek to renew our inner world or search for solutions to meet our human needs in the outer world, the potential for living in a state of natural good conduct with the Earth is greatly magnified through contemplative reflection and thoughtful encounters with nature. I like to call this special presence with the natural world ‘listening to the Big Quiet’.”

Lake describes the ways in which we may encounter the Big Quiet: “In the tapping and thrumming of raindrops gently falling on the lake. . . when we listen to leaves purling in the wind. . . as we watch a sunset over the ocean.” What she is describing are encounters with nature with space and time for reflection—to remind us of the great celestial collage of which we are a part; to ask ourselves when did we stop remembering the sun’s gift to us each day and where our food and water come from?

“The Big Quiet invites us to be present with ourselves and with our place, wherever we are, and to include the entire Earth community, down to the smallest of plants and animals, in our conversation. This is not a ‘romantic’ concept; on the contrary it is one of vital importance to our survival as a species.”

Quoting scientist Stephen Jay Gould, Lake identifies the nub of the problem for those of us whose lives are consumed by the industrial culture: “ ‘We cannot win the battle to save the species and environments without forging an emotional bond between ourselves and nature as well—for we will not fight to save what we do not love’. . . Without an emotional connection, we will not be motivated to care. Without knowledge of how we are connected. . . to nature and the larger cosmos, we will not easily find our way forward. A culture deprived of its origins and place in nature ultimately will not be sustainable.” (Emphasis added).

Around the Fire

Lake invites her readers to sit with her around a campfire she has nursed into life from wood shavings she has prepared with a well-worn knife given to her by a friend. Since the beginning of human time people have gathered around such fires to tell tales, to dialogue and dream. In her imagination she invites distinguished leaders and elders to join us and share their wisdom and knowledge.

The great Buckminster Fuller with his extraordinary encyclopedic grasp of design in nature is here and asks the question: “If the success or failure of this planet, and of human beings, depended on how I am and what I do, how would I be? What would I do?”

Dr. Joanna Macey, a general systems theorist and proponent of Deep Ecology, reminds us that we need to “recognize that denial itself is the greatest danger we face. We have the technology to make sweeping and effective changes. But not much can be done until we’re ready to acknowledge the situation we’re in.”

Nobel Prize winner Al Gore joins the circle and says: “Not too many years from now, a new generation will look back at us in this hour of choosing and ask one of two questions. Either they will ask, ‘What were you thinking? Didn’t you see the entire North Polar ice cap melting before your eyes? . . . Or they will ask instead, ‘How did you find the moral courage to rise up and solve a crisis so many said was impossible to solve?’” To this Lake adds: “Across the fire, I imagine the grandchildren of our generation looking at us with these questions in their eyes.”

Finally, she brings in Haudenasaunee Chief Oren Lyons who says, “We are the generation with the responsibility and the option to choose the Path of Life for the future of our children, or the life and path which defies the Laws of Regeneration.”

And with that warning in our ears and hearts we stare into the fire and let it slowly burn down. In the embers we see the question with which we began still glowing defiantly: Which way do we go from here? The insights and passion of Thomas Berry and Osprey Orielle Lake have shown clearly that the path is back along a return to reverence for nature. But how, exactly, is a confused industrial culture going to find that path?

The story continues.

The story of this blog so far tells how humanity strove to become a controlling force over nature. It is not a noble story; but neither can it be said to be an ignoble story. It is a mixed blessing. The despoiling of nature can be seen as a consequence of something greater—a seemingly pre-destined unfolding of the quest for consciousness to explain reality. In time it spans about three centuries, beginning when philosopher René Descartes in France and scientist/mathematician Isaac Newton in England opened up a vision of an Earth understandable by human reason. From there it was but a short step for entrepreneurial minds to assert that nature could be made to serve human purpose. Of course, we know now that this was wrong, but the course was set and followed. When seemingly unlimited sources of energy were discovered and combined with human ingenuity, a powerful new civilization spread around the world. We called it industrialism and today it denominates everything.

Industrialism became a new way of being on the Earth—one that could more fully exploit the bounty of nature. Sustained and accelerated by new concepts of specialized productive labour producing goods for sale in free markets, it came to be known as capitalism. A new discipline, economics, developed. It aimed to explain and manage this new form of human organization. And by and large the system worked well for many millions of people in many countries over many generations—but only if enterprise was disconnected from the limiting constraints of nature. The idea of limits was not compatible with a newfound sense of progress.

The new discipline of economics was embraced by politicians, industrialists and business leaders. Their minds were bemused into believing that civilization could defy the cycles and constraints of nature and surge forward into the future as a flood of never ending growth. Again, it seemed, except for periodic setbacks, to work well. Until we reached the 21st century.

Now evidence abounds that industrialism as we have known it is not sustainable very much further into the future. For those of us who lived the majority of our lives in the 20th century this is not a serious issue. The familiar trappings of material abundance will see us out. But for those of us who have a mind to care about what lies in store for our grandchildren the question is, “Which way do we go from here?”

The Dream of the Earth

Increasingly, the answer to that question is being sought in the science of ecology—in the context of how human activity is to be accommodated within the natural systems of the planet, including all other life forms that depend, along with us, on the healthy functioning of those ecosystems. Which brings me to the third E in the framework of this blog: Ecology as a determinant of human destiny.

We should understand from the outset that our consideration of ecology needs to go deeper than treating it as an objective science. A science it certainly is, and therefore amenable to the process of empirical investigation. As such, it is yielding valuable understanding about how ecosystems work and what that means for human settlement and activity. However, at a deeper level, underlying the collection and interpretation of scientific data, there is a profound sense that in this inquiry we are venturing into the realm of the sacred—the place where human reflection reaches to connect to something larger than itself. This is the place where I wish to begin.

To guide us into this reflection I can think of no better source than Thomas Berry, who was described by Newsweek as “the most provocative figure among this new breed of eco-theologians. . . a solitary American monk whose essays have aroused environmentalists like a voice crying for the wilderness.”

In 1988 a collection of Berry’s essays was published under the title, The Dream of the Earth. In the essay from which the book takes its title he sets out both the despair and hope for humanity. He begins gently then builds forcefully to his central argument.

“In this late twentieth century we are somewhat confused about our human situation. We need guidance. Our immediate tendency is to seek guidance from our cultural traditions. . . [But] our cultural traditions, it seems, are themselves a major source of our difficulty. It appears necessary that we go beyond our cultural coding. . . we need to go to the earth, as the source when we came, and ask for its guidance, for the earth carries the psychic structure as well as the physical form of every living being upon the planet. . . The human is less a being on the earth or in the universe than a dimension of the earth indeed of the universe itself.”

In these few short sentences Berry has established the central argument of the ecological as opposed to the industrial view of humanity. The human being is not just physically but psychically connected to the earth. Then he goes on to describe the consequences of ignoring that bond.

“Our secular, rational, industrial society, with its amazing scientific insights and technological skills, has established the first radically anthropocentric society and has therefore broken the primary law of the universe, the law of the integrity of the universe. . . The immediate advantages of this new way of life for its prime beneficiaries have been evident throughout these past two centuries. But, now, suddenly, we begin to experience disaster on a scale never before thought possible.”

From there Berry goes on to catalogue what we thought were our great achievements “to re-engineer the planet” all in the name of “this magical word progress!” But what we did not understand was that this sense of achievement was grounded in illusion.

“What we seem unwilling or unable to recognize,” says Berry, “is that our entire modern world is itself inspired not by any rational process, but by a distorted dream experience, perhaps by the most powerful dream that has taken possession of the human imagination. Our sense of progress, our entire technological society, however rational in its functioning, is a pure dream vision in its origin and in its objectives. . . The story of this dream vision. . . has become the central story of the human community. . . The difficulty of our times is our inability to awaken out of this cultural pathology.”

And what are the physical manifestations of this cultural pathology? Berry asserts their gravity in short, sharp, stabs of acid prose.

“We are changing the chemistry of the planet. We are altering the great hydrological cycles. We are weakening the ozone layer that shields us from cosmic rays. We are saturating the air, the water, and the soil with toxic substances so that we can never bring them back to their original purity. We are upsetting the entire earth system that has, over some billions of years and through an endless sequence of experiments, produced such a magnificent array of living forms, forms capable of seasonal self-renewal over an indefinite period of time.”

Strong words, but Berry is just warming to his subject!

“The disastrous consequences [of our attitude and behaviour] on the integral functioning of the earth [and] on our human destiny. . . are now becoming manifest. The day of reckoning has come. In this disintegrating phase of our industrial society, we now see ourselves not as the splendour of creation but as the most pernicious mode of earthly being. We are the termination not the fulfillment of the earth process. . . We are the affliction of the world, its demonic presence. We are the violation of earth’s most sacred aspects.”

However, as deep as Berry’s despair of the human impact on the planet might be, he is not without hope. He turns next to considering the way out.

“In moments of confusion such as the present, we are not left simply to our own rational contrivances. We are supported by the ultimate powers of the universe as they make themselves present to us through the spontaneities within our beings. . . The supreme need of our times is to bring about a healing of the earth through this mutually enhancing human presence to the earth community. To achieve this mode of presence, a new type of sensitivity is needed, a sensitivity that is something more than romantic attachment to some of the more brilliant manifestations of the natural world, a sensitivity that comprehends the larger patterns of nature, its severe demands as well as its delightful aspects, and is willing to see the human diminish so that other life forms might flourish.”

Now he has come to it. Human survival depends on our rethinking of the intrinsic values of the natural world, as well as the value we might accord to our own human culture.

“Two radical positions—the industrial and the ecological—confront each other, with survival at stake: survival of the human at an acceptable level of fulfillment on a planet capable of providing the psychic as well as the physical nourishment that is needed. No prior struggle in the course of human affairs ever involved such issues at this order of magnitude. If some degree of reconciliation has taken place, it remains minimal in relation to the changes that are needed to restore a viable mode of human presence to the earth.”

That was said in 1988. Some progress has been made since then in understanding our predicament, but not a lot in correcting it as Berry would have us do. The last paragraph of his essay resonates with his still unanswered challenge.

“In relation to the earth, we have been autistic for centuries. Only now have we begun to listen with some attention and with a willingness to respond to the earth’s demands that we cease our industrial assault, that we abandon our inner rage against the conditions of our earthly existence, that we renew our human participation in the grand liturgy of the universe.”

The Great Work

Writing a decade later at the turn of the new millennium, Berry published his manifesto for what we must do, and called it The Great Work: Our Way into the Future (1999). Reflecting on the great work of previous periods in human history—like “the Great Work of the classical Greek World” that created the Western humanist tradition, and “the Great Work of Israel in articulating a new experience of the divine in human affairs”—Berry sets out the challenge for our own time in clear unambiguous terms: “The Great Work now, as we move into a new millennium, is to carry out the transition from a period of human devastation of the Earth to a period when humans would be present to the planet as in a mutually beneficent manner.”

Berry has an epochal view of this moment in time: “The Great Work before us. . . is not a role we have chosen. It is a role given to us, beyond any consultation with ourselves. We did not choose. We were chosen by some power beyond ourselves for this historical task.” In Berry’s sense of history civilization moves forward through epochal moments, when conditions have regressed into a “Dark Age” of ignorance and new generations step forward to lead humanity out of its impasse. At these times the generations alive must see themselves not only as chosen to participate in the great work to be done, but as sustained “and cared for and guided by these same powers that bring us into being. . . We cannot doubt that we too have been given the intellectual vision, the spiritual insight, and even the physical resources we need for carrying out the transition that is demanded of these times.”

What an inspiration these words of Thomas Berry are to those who read this blog and to the countless thousands of others worldwide who are stepping forward to halt the “industrial assault” on the natural world! In such an inspired vision lies the best hope for our grandchildren. Every one of us has a role to play—and we are never acting alone, but in unison, in a “capacity for relatedness,” which is woven into the fabric of the universe in a wondrous dance of participation.

Berry’s contribution to the transcendent change for which he argues is much greater than his foundational concepts about the human-nature continuity. He has much to say in The Great Work about the specific transformations required in industrially acculturated institutions: reforms in education, jurisprudence, ethics, governance and corporate activity. These specifics will be covered in later posts as we explore initiatives to be undertaken in the E of enterprise in the framework of this blog. For now we need to understand the foundational insights articulated so passionately by Berry that must underlie the actions we need to take.

Commenting on Berry’s great contribution to transformational ecological thinking, environmentalist Richard Louv in The Nature Principle: Reconnecting with Life in a Virtual Age (2012) cites an interview with Berry in 1999 in which he spoke about the inner core of his belief: “If we don’t have certain outer experiences, we don’t have certain inner experiences, or at least, we don’t have them in a profound way. We need the sun, the moon, the stars, the rivers and the mountains and the birds, the fish in the sea, to evoke a world of mystery, to evoke the sacred. It gives us a sense of awe. There is a response to the cosmic liturgy, since the universe itself is a sacred liturgy.”

What does he mean, “the universe itself is a sacred liturgy?” We must remember that Thomas Berry was a Roman Catholic priest of the Passionist order, and as such liturgy—the prescribed order for public worship—was important to him. But Berry, the cosmologist, saw beyond the confines of his Christian tradition, to the great new creation story of the universe revealed by modern science. And his interpretation of his scientific account of the Big Bang and the formation of the galaxies carries with it the mystical insights of the spiritual mind.

Not only, he says, was ”the flaring forth of the primordial energy” the beginning of the Earth story, it was also “the beginning of the personal story of each of us, since the story of the universe is the story of each individual being in the universe.” The sacred liturgy of the universe is the revelation over eons of time that “inherent in the original flaring forth” were the “shaping forces” that “brought forth the galaxies, the Earth, the multitude of living species” and also the human intelligence that now reveals the new creation story as the universe becomes conscious of itself. We, humans, are the consciousness of the universe fully invested with all of its transcendent magnificence, and we are not about to compromise our sacred part in this new creation story by allowing the lesser aspects of our intelligence that support the “assault of industrialism” to triumph over our sacred heritage.

If you understood all that, then you will know why Thomas Berry, though he was filled with despair at what he saw happening to the natural world during his lifetime, was optimistic at the end of his life about prospects for the future. Richard Louv, whom I mentioned above as the author of The Nature Principle, first met Berry in 2005 when Berry was ninety-one years old. Right away, Louv reports, the old man began to talk about the future: “Everything we discuss now should be about the twenty-first century. . . The great work of the twenty-first century will be to reconnect to the natural world as a source of meaning.” A few years later in 2009 Louv visited Berry for the last time, shortly before his death. Even at that great age, the grand old eco-theologian said that he felt an urgency to “go out into the natural world every day, no matter what the conditions are” because “the giftedness continues.”

Uprisings for the Earth

I have devoted so much space in this post to the teaching of Thomas Berry because his insights go to the heart of what we must do in the decades ahead to preserve a viable future for humanity in the natural world. Berry sensed an “inner rage” in human beings of the industrial age against nature because we want to escape the limits that nature imposes. We want to be better than nature. But what we must be is in nature: to accept the earthquakes, the hurricanes, the pestilences and the privations along with the awe and wonder and the marvellous nutritional abundance of the land and the oceans. Indeed, “the giftedness continues.” Our task is to learn again how to receive and use the gifts.

Another voice to add resonance to Berry’s message is that of artist/sculptor/environmentalist Osprey Orielle Lake, who brings her feminine sensitivity to the call for humanity’s reconnection to the natural world in Uprisings for the Earth: Reconnecting Culture with Nature (2010). Taking off from Berry’s distinction between our inner and outer worlds, she says simply: “My thesis is this: whether we seek to renew our inner world or search for solutions to meet our human needs in the outer world, the potential for living in a state of natural good conduct with the Earth is greatly magnified through contemplative reflection and thoughtful encounters with nature. I like to call this special presence with the natural world ‘listening to the Big Quiet’.”

Lake describes the ways in which we may encounter the Big Quiet: “In the tapping and thrumming of raindrops gently falling on the lake. . . when we listen to leaves purling in the wind. . . as we watch a sunset over the ocean.” What she is describing are encounters with nature with space and time for reflection—to remind us of the great celestial collage of which we are a part; to ask ourselves when did we stop remembering the sun’s gift to us each day and where our food and water come from.

“The Big Quiet invites us to be present with ourselves and with our place, wherever we are, and to include the entire Earth community, down to the smallest of plants and animals, in our conversation. This is not a ‘romantic’ concept; on the contrary it is one of vital importance to our survival as a species.”

Quoting scientist Stephen Jay Gould, Lake identifies the nub of the problem for those of us whose lives are consumed by the industrial culture: “ ‘We cannot win the battle to save the species and environments without forging an emotional bond between ourselves and nature as well—for we will not fight to save what we do not love’. . . Without an emotional connection, we will not be motivated to care. Without knowledge of how we are connected. . . to nature and the larger cosmos, we will not easily find our way forward. A culture deprived of its origins and place in nature ultimately will not be sustainable.”

Around the Fire

Lake invites her readers to sit with her around a campfire she has nursed into life from wood shavings she has prepared with a well-worn knife given to her by a friend. Since the beginning of human time people have gathered around such fires to tell tales, to dialogue and dream. In her imagination she invites distinguished leaders and elders to join us and share their wisdom and knowledge.

The great Buckminster Fuller with his extraordinary encyclopedic grasp of design in nature is here and asks the question: “If the success or failure of this planet, and of human beings, depended on how I am and what I do, how would I be? What would I do?”

Dr. Joanna Macey, a general systems theorist and proponent of Deep Ecology, reminds us that we need to “recognize that denial itself is the greatest danger we face. We have the technology to make sweeping and effective changes. But not much can be done until we’re ready to acknowledge the situation we’re in.”

Nobel Prize winner Al Gore joins the circle and says: “Not too many years from now, a new generation will look back at us in this hour of choosing and ask one of two questions. Either they will ask, ‘What were you thinking? Didn’t you see the entire North Polar ice cap melting before your eyes? . . . Or they will ask instead, ‘How did you find the moral courage to rise up and solve a crisis so many said was impossible to solve?’” To this Lake adds: “Across the fire, I imagine the grandchildren of our generation looking at us with these questions in their eyes.”

Finally, she brings in Haudenasaunee Chief Oren Lyons who says, “We are the generation with the responsibility and the option to choose the Path of Life for the future of our children, or the life and path which defies the Laws of Regeneration.”

And with that warning in our ears and hearts we stare into the fire and let it slowly burn down. In the embers we see the question with which we began still glowing defiantly: Which way do we go from here? The insights and passion of Thomas Berry and Osprey Orielle Lake have shown clearly that the path is back along a return to reverence for nature. But how, exactly, is a confused industrial culture going to find that path?

The story continues.